If you were to write a fictional life story about an African American woman who escaped poverty to dance on the Broadway stage, moved to Paris to become an international celebrity and a film star, then served as a spy for the French Resistance during World War II, you would think it was a work of pure fiction. But it was all true. Josephine Baker lived all of that… and much more.

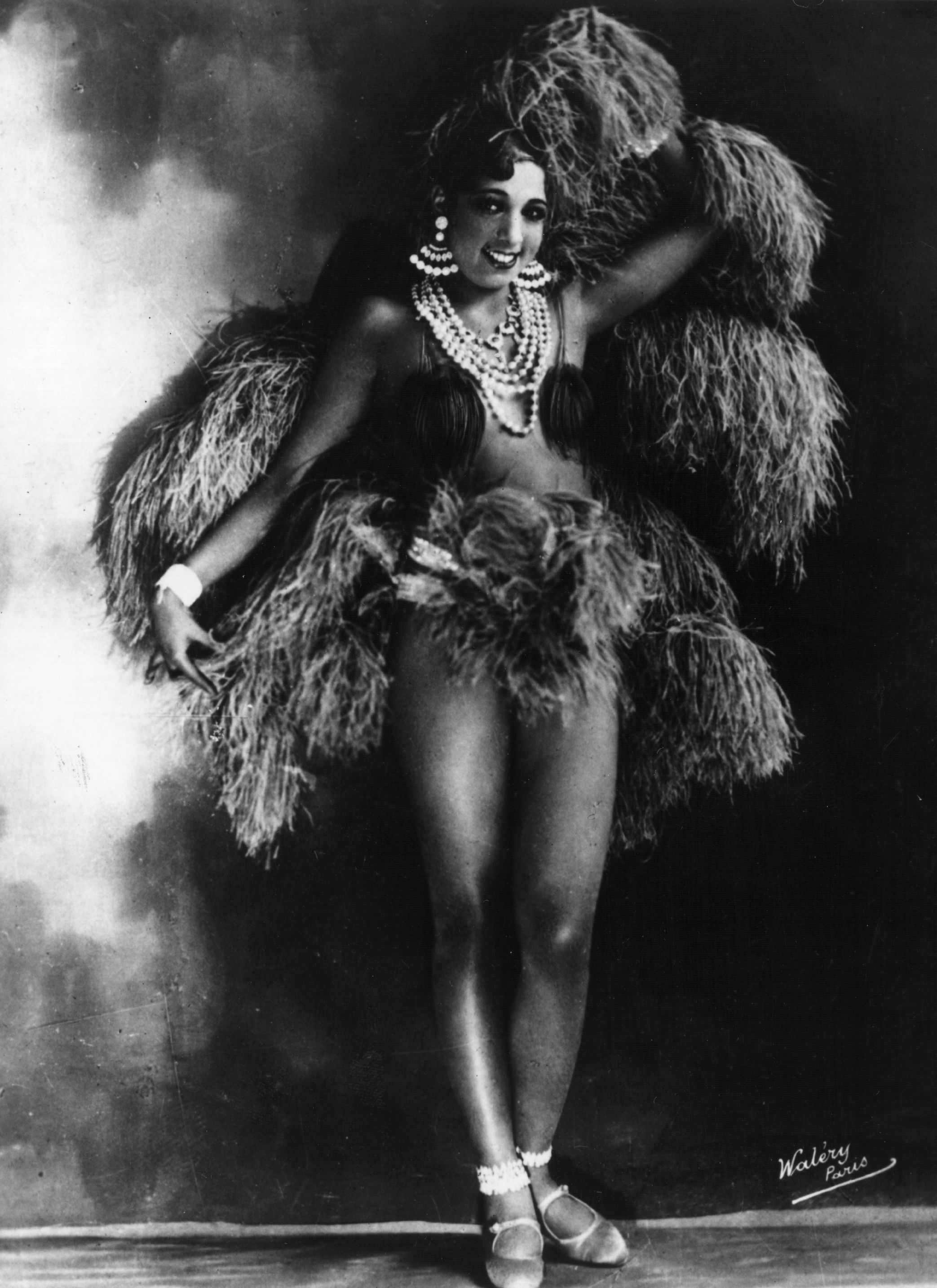

Josephine Baker c. 1925. [Getty Images]

Josephine was born Freda Josephine McDonald in St. Louis, Missouri on June 3, 1906. Her mother barely scratched out a living as a laundry worker after Josephine’s father abandoned the family shortly after she was born. From the age of eight, she began to ease the financial burden on her mother by taking on menial jobs. Josephine got married very young, but the marriage lasted only a year. Soon after she focused on honing her skills as a dancer and worked with a trio of entertainers, the Jones Family Band.

It did not take long for the Dixie Steppers, a traveling vaudeville troupe, to encounter young Josephine’s charismatic onstage presence and knack for being both humorous and seductive. The ever-resourceful girl jumped up on stage while the group was performing in St. Louis for an on-the-spot audition. The audience cheered on Josephine’s comical dance, and she secured a spot in the troupe the very next day.

While touring in Philadelphia, Josephine (a mere 15 years old at the time) met and married railroad worker William Baker. Her second marriage was short-lived, like her first, but she kept the last name Baker for the rest of her professional career.

Josephine Baker in the 1930s. [Getty Images]

In 1922, Josephine arrived in New York City just as the Harlem Renaissance was blossoming. During that time, Harlem became a mecca of African American culture. There Josephine rubbed shoulders with prominent African American luminaries, performed at the Plantation Club in Harlem, and danced to bands led by Duke Ellington and other American jazz musicians.

She longed to perform on the Broadway stage and, after many rounds of auditions, she joined the chorus line of a highly successful Broadway revue called Shuffle Along. To stand out from the other members of the chorus line, Josephine introduced humor into her dance routine, which became a major part of Shuffle Along. When the hit Broadway show was booked to perform in Paris, she was ready for a change.

Little did she know that the trip would change her life forever.

Josephine Baker, August 1933. [Getty Images]

When she stepped off the ship in 1925, Josephine fell in love with Paris, and Paris fell in love with her. She landed in the forefront of French psyche because, to her new audience, this young African American entertainer embodied the “Roaring ‘20s.”

In 1926, at the Folies Bergère music hall, Josephine’s fame reached new heights as she created an act in a now-iconic costume of her own creation that included a skirt decorated with artificial bananas—one of her many risqué costumes. When she sang and performed the exotic Danse Sauvage, she made an immediate impression on French society.

Her performance was such a hit that it was labeled a must see for all of Paris. American writer Ernest Hemingway, then a new author who lived in the city, described her as “the most sensational woman anyone ever saw.” Josephine became the toast of Paris, and every artist there from Pablo Picasso to Jean Cocteau wanted to meet her. Legend has it that she received more than 1,000 marriage proposals.

Josephine Baker triumphs in Paris during the Jazz Age. Josephine in one of her elaborate costumes, c. 1930. [Getty Images]

Josephine’s movie debut took place in 1927 with the French silent film, La sirene des tropiques (Siren of the Tropics). In 1936, riding high on the popularity she was enjoying in France, Josephine visited the States to perform in the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway. She had hoped to establish herself as a major star in her home country. Unfortunately, her performance was met with hostility and racism as New York theater critics were especially cruel in their reviews.

Heartbroken, Josephine went back to Paris doubting she would ever return to the U.S. Soon thereafter, she became a citizen of France.

France declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939. Inspired by the love for her new country and antipathy for Germany’s racist Nazi regime, Josephine sang and danced to raise money for the French army. Once Paris fell to the Germans, she moved to her chateau in the south of France and sheltered other refugees. It was not long before Josephine was drawn into the world of espionage.

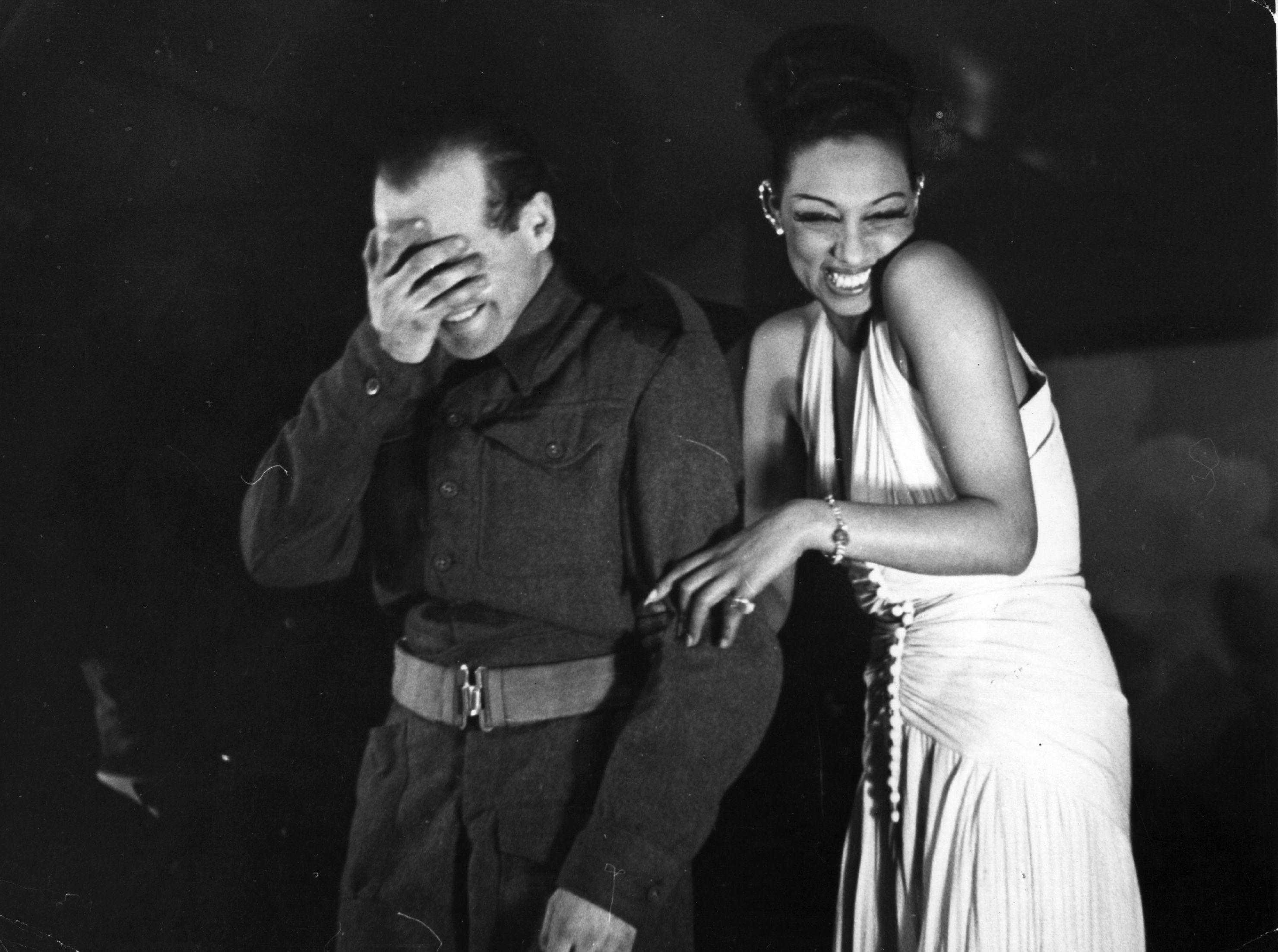

Josephine Baker amuses a soldier with a song while entertaining the troops at a London victory party, 1945. [Getty Images]

French counterintelligence officer Jacques Abtey was struck by Josephine’s keen interest in helping France’s war efforts and set up a meeting with her. She readily agreed to become an asset for the French Resistance, reportedly raising her glass of champagne in a toast, “To France!”

As an entertainer and celebrity, Josephine could easily move around the country and socialize with German, Italian, and Japanese bureaucrats at diplomatic functions, night clubs, and in café society without raising suspicion. She charmed and flattered guests, all the while collecting secrets on enemy troop movements and the harbors and airfields used by the Axis powers.

When German High Command received information that Josephine was hiding resistance fighters, the Germans paid a visit to her chateau. Against the odds, she deflected their suspicion but knew it was time to leave France. Josephine and Abtey fled the country. With them they carried dozens of classified documents and intelligence, all written in invisible ink on her sheet music.

Exiled from France, Josephine continued working for the French Resistance after relocating to Lisbon, Portugal and then to North Africa. Under the guise of embarking on an international singing tour, Josephine traversed neighboring countries and beyond gathering intelligence that she passed along to her French handlers. Some of the information she shared on area tides, beaches, and enemy defenses helped support an Allied amphibious invasion of North Africa, known as Operation Torch, in November 1942.

Josephine Baker smiling, proudly wearing her French Air Auxiliary Lieutenant’s uniform, April 25, 1945. [Getty Images]

After D-Day on June 6, 1944 and the subsequent liberation of Paris, Josephine returned to her beloved city proudly wearing her French Air Auxiliary Lieutenant’s uniform. Touched by how Paris had suffered under Nazi occupation, she sold pieces of jewelry and other valuables to raise money to buy food for the poor. Never once did she ask for or receive compensation for her wartime activities.

In 1945, General Charles de Gaulle, who led the Free French Forces and the provisional government, personally thanked Josephine for her heroic efforts during the war and awarded her with the Croix de Guerre and the Rosette de la Resistance. De Gaulle also awarded her a Chevalier de Legion d’Honneur (National Order of the Legion of Honor), the highest order of merit for military and civil action.

Josephine Baker, 1949. [Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division]

Josephine lived in France until her death in 1975, but she was a strong advocate for the American Civil Rights Movement. When invited to perform in the U.S., she refused to do so in front of segregated audiences. Yet international fame did not shield Josephine from experiencing discrimination herself.

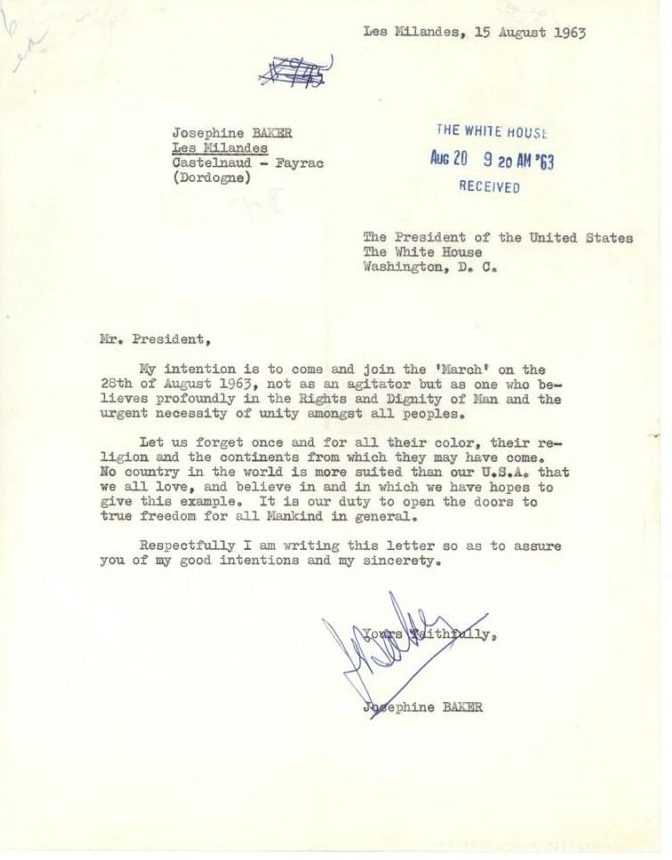

Letter from Josephine Baker to President Kennedy, August 15, 1963, ahead of her arrival for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. [National Archives Rediscovering Black History via Kennedy Library]

Crowds arriving at the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool on the National Mall during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. [Library of Congress, Photo by David L. Harris]

During the March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, D.C. in 1963, Josephine stood alongside Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. In a speech in front of a sea of people, she declared:

“You know, friends, that I do not lie when I tell you I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out ‘cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world…”